My friend Dwaraknath Reddy in one of his short but perceptive and thought provoking essays, describes a reverie, in which a child asks of him “Sir, what is the colour of the wind ? “

This of course, is not a simple, child-like question, but a serious one. Nor does it have a simple or easy answer. The question gets added depth and poignancy here, from the fact that the child asking the question is blind. For in the inner world of such a child, words and meanings are often not associated, and the child knows of colour as only a meaningless word, not a meaningful experience. Indeed the question raises a whole lot of more basic questions for which scholars and scientists the world over are still struggling to find answers. They are questions on perception and cognition : what precisely do the senses convey to us and how exactly do we interpret these sensory inputs and and respond to them ?

A considerable body of fact and inference has accumulated through scientific studies of these questions over the last hundred years or so. One important conclusion is that the cognitive centres of the brain arrive at an integrated view of the inputs streaming in concurrently from all the sensory organs, and give an integrated response to them. This conclusion has obvious but far-reaching implications for our understanding of the learning process and our approach to designing the teaching process.

One implication is that each sensory input, however strong or weak, makes its own indispensable contribution to the integrated picture developed by the cognitive centres, and that the poor content of one input is compensated or complemented by the richer content of the others. We are familiar for instance, with how the spoken words we hear, are often augmented or substituted by the unspoken words of the body language or of sign language. Or how a visual diagram conveys a concept more readily than an oral description. It follows from this that our teaching strategies should address the strengthening, not only of the weaker sensory inputs, but also of the compensatory or complementary potentials of all of them. Indeed much of the contemporary strategies of teaching rest upon this finding.

It is important for us to take stock of where we stand today in respect of our understanding of and response to these inner processes involved in learning and teaching. And it may be useful to begin by taking note of some fundamental truths that come to us from time immemorial from the way of Nature, as instinctively followed by the child’s teacher, the mother, and as consciously institutionalised in ancient tradition. The first truth proceeds from the fact that sound is the first sense through which the new born baby and the mother establish two-way communication. Sounds, at first meaningless, are gradually shaped into words, which, with the aid of memory, are systematically associated in the child’s mind with corresponding experiences and thereby invested with meaning. This learning process through the medium of sound is concurrently augmented by the sense of touch, through the soft comfort and warmth of close contact with the mother’s body , while the sense of taste and hunger and need for emotional reassurance are satiated from suckling at her breast. The sense of sight comes into play more gradually into the baby’s experience, with visual images getting associated with corresponding sounds, words and meanings. At least initially, then, sound remains the prime vehicle of word and meaning and therefore of learning, while touch and sight play a supportive but significant role in augmenting the effectiveness of the sound based process. Of course, if a child is born deaf, sight becomes the primary input. The mother fine-tunes the same general approach with the arrival of each of her additional children, though in the case of a child with a disability, she does innovate and introduce appropriate changes in emphasis and method. Be it noted incidentally, that the able siblings play an important supportive role in augmenting the teaching efforts of the mother. And indeed, this is a special and valuable experiential role that is lost to normal children when there are no children with disabilities among their siblings at home or among their peers later in the schools they attend. Here then, is Nature’s way of the learning and teaching process at its most basic and best.

Ancient tradition too consciously remained faithful to this way of Nature. The word transmitted through sound, by speech and hearing, remained for a long time, the basic strategy for learning and teaching and for the dissemination of information and knowledge in society. The Vedic tradition in India, specifically institutionalised this as a comprehensive, scientific discipline, for preservation and transmission of the ancient heritage of higher knowledge. Those ancient teachers who raised language to such a high level of scientific perfection, could quite certainly have adopted prevailing writing systems or or even developed new ones. Yet, they consciously eschewed a strategy of reading and writing even after the introduction and spread of writing systems, and (almost obsessively) maintained the oral / aural tradition of learning / teaching. Some social historians of course, ascribe this to the desire of the priestly class to maintain knowledge as their close preserve and thereby maintain their social primacy. A more charitable view would concede to the true teachers of this tradition, an intellectually honest conviction that at least in the realm of higher knowledge related to religion and philosophy, which rested solely on thought and rigid logic, and personal experience in the areas of faith, devotion, emotion and intuition, there was really no adequate substitute for the spoken word as the most basic strategy for teaching and learning for all time. It was this conviction that was sanctified and institutionalised in the teacher-pupil, the Guru-Sishya, relationship.

The development of trade and administration paved the way for development of writing systems and the need for reading skills, as basic essentials in the new socio-economic environment. This saw the evolution of the formal educational system with the teacher using reading and writing as the primary vehicle of the formal education process, taking over from the mother’s way of reliance initially on speech and hearing, and later, sight as well. Beyond doubt, the new skills of reading and writing triggered the unparalleled proliferation of knowledge, and altered the course of human development and world history, obviously with far-reaching benefit to humanity. But it also brought in its unintended train, a new range of learning difficulties for many children. Our response here has been to provide personalised, specialised teaching, where there is a return to the primacy of the spoken word. This poses a basic question : does not reading and writing add an additional and complex learning load of visual recognition to the basic mental load of establishing the association of words and meanings ? There is another incidental question : does not the environment of visual learning and experience also provide visual distractions that weaken the basic learning process of attentive hearing, of pointed attention to word and meaning ? These questions are intended to point, not to the validity or relative value of different learning methods based on sight, sound and touch. but to the complexities that are involved in understanding the true learning potentials and limitations of the different faculties in different individuals. These questions emphasise how important it is that all faculties be consciously brought into an effective holistic harmony to serve the processes of learning and teaching.

Let us take our approach to teaching the visually impaired. A child that has no sight has necessarily to fall back on the learning potentials of the faculties of sound and touch. That our teaching strategy inevitably falls back on the hearing faculty is to the good, but unfortunately and incidentally, this strategy also brings into play a bias, perhaps unintended, against use of tactile solutions. This is because, as already stated, sound has always been the most natural and effective teaching route. Lessons can be imparted by voice, directly in person or later through recordings, or over distances, by wire or wireless. Also, the hearing faculty has been more widely studied and understood than the tactile faculty and hearing-based aids have therefore been more widely developed. Thus, for both the blind student and his teacher, a cassette player is more readily preferred learning or teaching solution than a braille book. But simple biases of this kind have complex consequences that are not readily apparent, and beg a number of deeper philosophical questions.

To get a better understanding of the mechanisms, limitations and potentials of the tactile faculty and also of the deeper basic role of tactile input at the level of cognition we may begin with a recognition of the fact that the sense of touch has some unique and critical features that distinguish it from all the other senses. Firstly, the sense of touch pervades the entire skin surface of the body. Tactile inputs of pressure, pain, heat and cold can be generated through contact at every part of the body. And secondly, the neural and muscular network of the entire body participates in processing tactile inputs and output responses to them. On the other hand, the eye and the ear are specific, specialised, localised organs that handle visual and auditory input and each of them has a single direct neural input channel to the brain. Of course, within the total tactile sensory surface of the body, the hands and fingers can in a broad sense, be taken to constitute the specialised organ of touch, as indeed was suggested by Katz, a German psychologist in 1925.

What makes the hands and fingers so special ? First, the cutaneous surface of the hands and fingers are more thickly padded with fat and tissue than any other part of the cutaneous surface of the body. Also the palm and the finger surfaces are marked by patterns of ridges, those patterns that are unique enough to provide foolproof identity of the individual. And these ridges have the highest concentration not only of nerve endings but also of sweat glands which irrigate and lubricate the entire palmar and finger surface with sweat flowing through the inter-ridge channels. All these features clearly have their own special effect on the tactile sensitivity and efficiency of the surface of the hands and fingers.

What is it in these structures of the sense of touch that offer learning potentials to persons with visual or other disabilities ? In a general sense the cutaneous surface of the entire body is always at the service of the individual. Any part of his body can tell him what the weather is like, hot, cold, sunny, or rainy. The soles of the feet tell him whether the ground he walks on is soft, slushy, slippery or sloping. And as his feet feel their way forward, they alert him to obstacles. But even more importantly, the warm cuddling of a mother or the touch-based training of the Special Educator carries to a child a world of emotionally rich body language, often more eloquent than the visually communicated or orally articulated word. These facts indeed underlie much of the teaching methodology for children who are deaf-blind or have other multiple disabilities.

Let us consider the more formal specialised process of learning to read

and write, which involves, in the case of the blind, the use of braille

through the use of the sense of touch of the fingers. In braille, each

letter of the alphabet is represented by a unique pattern of dots

embossed on paper. These dots are in one or more of six positions arranged

in two columns and three rows within a standard area called a cell. The

dimensions of a cell are such as will fall within the sensing pad of the

reading finger. In the braille context, the process of embossing a line

of cells on paper using a stylus, corresponds to writing, and the process

of sensing the cell content of a line of cells with the finger corresponds

to reading. Here for instance, is a visual repesentation of two lines of

text in Braille

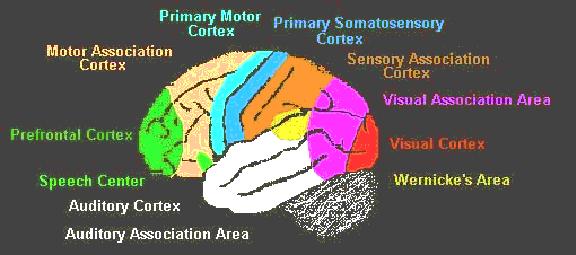

What happens when a blind person reads these lines in their embossed form with the touch of his finger, from left to right ? The finger transmits signals from the nerve endings on it’s surface, to an appropriate cognitive centre in that remarkable instrument that we are all endowed with by Nature, the brain. The following is a schematic diagram of the brain depicting what science is able to tell us about the brain and it’s cognitive centres.

But what science tells is still very little about the processes of interpretation and understanding. It does not tell us how precisely the signals coming from the finger tip sensing the above braille lines are interpreted and read as :

These are difficulties that demand scientific and sensitive understanding and patient effort on the part of the teacher of the blind. Where a teacher has these qualities, the results in the pupil can be remarkable, as so eloquently shown in the case of Helen Keller. But gifted teachers with these qualities are not easy to come by, and all too often we have teachers who are unaware, if not insensitive, and therefore add to the host of negative forces and factors that operate against the needs of the visually impaired.

One such negative force, surprisingly, comes from technology. Impressive as the accomplishments of technology are, there is no denying the fact that it is driven more often by the pursuit of profit than by sensitive concern for human need. Thus, in offering solutions for the blind, technology prefers to address the easier and more profitable solutions based on hearing than those based on touch. Typically, the cassette player is offered as the easier alternative to the braille book. Today the juggernaut of technology moves on relentlessly and in a paradigm jump from the cassette player to the computer, offers even more powerful teaching tools that largely provide speech and hearing based solutions. A sad result, unintended perhaps, is that such solutions threaten to push braille further into the background, and will perhaps ultimately let it pass into history. Is there wisdom in thus letting the sense of touch be pushed into a lower priority in the learning process ? Let us consider the deeper implications of this question.

The sense of touch is far too valuable and integral member of the total sensory resource system of an individual for us to attempt to prioritise its role. The blind have to heavily rely on the sense of touch, not just in the context of reading and writing, but in helping to interpret and understand a whole host of everyday situations and activities, as briefly indicated earlier. Surely therefore, it makes sense to train this sense systematically, so that it leads to heightened cognitive efficiency in every such situation and activity. More than as a specific enabler of word-based communication, training with braille may well have a deeper value as a generic enhancer of tactile sensitivity and cognitive efficiency, and this is a possibility that should be but explored and exploited , not discounted.

The foregoing narrative draws much from a 1996 doctoral thesis in the University of Birmingham (UK) by Pamela Lorimer which presents an excellent overview and evaluation of all research and development effort on tactile modes of reading braille. She cites the words, ringing loud and clear, of David Blunkett, the visually impaired Labour Party M.P. in the British House of Commons, who is currently Home Secretary in the British Government : “With all its quirks and frustrations, braille is essential. Without it, it would be very difficult for me to do my job. I use it for making notes, for preparing speeches …… I enjoy reading books ….. To me, braille is an essential tool in everyday life, whether in work, recreation or normal family activity …… the tremendous advantages massively outweigh the difficulties …..”. These eloquent words tell us how much a sustained and pointed development of the sense of touch through the use of braille has helped Blunkett gain success in public life and fulfillment in personal life. These words give us a sense of true perspective : Lorimer’s own closing words in her thesis are therefore no less significant : “ ….. braille has both a history and a future”

The comments made here on technology are not in any way intended to eschew the solutions or possibilities it offers. The need quite certainly is to foster all the positive gains of technology. Today’s interactive, multi-media capabilities of the computer, are indeed providing very powerful aids for multi-modal learning. But the preference for sound-based solutions over touch based solutions for the blind is getting sharper. Already, thanks to this technological bias, one sees in the USA, a sad social trend of what has been described as a “benign neglect of braille”, which computerised braille soutions cannot hope to arrest, given their high cost. We should have technology by all means, but without letting it compromise an understanding of the basic roles and potentials of human faculties by prioritising their utility in terms of a commercial value system. Clearly we need technology with a human face and this plea has a ring of anguish when it comes from the world of the blind. Surely the potentials of technology can be pressed into producing less expensive braille output devices; or solutions that might produce, not braille, but normal alphabetical text in embossed form that admits of tactile reading. Surely classroom equipment can be designed and produced inexpensively today, where audio-visual teaching can be transmitted to reach not only normal children, but simultaneously reach disabled children in electronic form, through appropriate assistive devices, within the same classroom setting. Surely solutions are possible that would obviate to a considerable extent, the need to separate children into separate learning streams based on differences in ability and disability.

The foregoing perspectives are indeed a plea for greater integration of our existing teaching methodologies and arrangements. Modern analytical studies have inevitably been driving us down the reductionist road, into specialisations of knowledge and method, which their votaries practice and defend with fierce and narrow loyalties. Separating the disabled from the normal, we have evolved the mantra of Special Education with different specialisations in organisation and method addressed to different disabilities and degrees of disability. And in the background we hear a weak refrain, almost a lost voice, pleading for integration. People who know and people who care are convinced that we must halt this divisive trend; and evolve a new approach that concurrently mobilises the full potential of all sensory inputs and not a selective use of some, and where all children, able or disabled, can merge seamlessly into a new model of a common holistic learning environment.

But is it not strange that we still search for a new holistic model,

when it is clear that the home and the mother constitute the

school and the teacher of a near perfect model of a complete integrated

educational system; a model that addresses all faculties of each

child and of all children together in the home, on such a holistic approach,

and not only imparts knowledge and skill but also instils the

values of care and compassion, all this with total commitment and at no

cost. Should we not invest our schools and teachers with this spirit

of integration finding expression in much the same way. Surely, when we

refer to our school as our “Alma Mater”, we are investing it with some

of the matchless attributes of our first school and teacher, the home and

the mother ? This should give us food for thought.